My mother’s maiden name was Elder. When I was a child we possessed a family treasure, a book written by one of our ancestors (I believe it was Inmates of My House and Garden). I took it to school to show off and managed to lose it.

After I grew up, I sought to atone for this dereliction. As a doctoral candidate I travelled to Wales in 1997 to attend the founding conference of UK ASLE (Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment) at Swansea. It occurred to me that I may be able to track down a copy of the lost book in the U.K., so I approached a friend and colleague who worked in the library at Murdoch University and asked how I might go about searching.

We sat together while he typed her name into World Catalogue of Books and were stunned when the screen started scrolling showing multiple titles and multiple editions and translations into German and French. An unexpected treasure trove.

The thing is I had grown up to be a writer of natural history stories, the author of Deadly Beautiful - Vanishing Killers of the Animal Kingdom, and the editor of the journal Landscope in its earliest years of publication..

I turned to my friend and said, “Well this certainly puts a new slant on the nature versus nurture debate.”

Knowing my writing, he did not miss a beat, replying, “Bugger that, what about the recycled souls debate?”.

I paid a pretty sum in London for her memoir. The price was high because it had a (rather patronising) introduction and epilogue by her nephew Sir Edmund Gosse, who had deigned to sign the title page.

He was the more famous personage. But it was her story that was priceless to me.

After I grew up, I sought to atone for this dereliction. As a doctoral candidate I travelled to Wales in 1997 to attend the founding conference of UK ASLE (Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment) at Swansea. It occurred to me that I may be able to track down a copy of the lost book in the U.K., so I approached a friend and colleague who worked in the library at Murdoch University and asked how I might go about searching.

We sat together while he typed her name into World Catalogue of Books and were stunned when the screen started scrolling showing multiple titles and multiple editions and translations into German and French. An unexpected treasure trove.

The thing is I had grown up to be a writer of natural history stories, the author of Deadly Beautiful - Vanishing Killers of the Animal Kingdom, and the editor of the journal Landscope in its earliest years of publication..

I turned to my friend and said, “Well this certainly puts a new slant on the nature versus nurture debate.”

Knowing my writing, he did not miss a beat, replying, “Bugger that, what about the recycled souls debate?”.

I paid a pretty sum in London for her memoir. The price was high because it had a (rather patronising) introduction and epilogue by her nephew Sir Edmund Gosse, who had deigned to sign the title page.

He was the more famous personage. But it was her story that was priceless to me.

The Cambridge Connection

Many decades later, my niece Isobel discovered a blog about Eliza Elder Brightwen in the Her Story series "exploring the stories of fascinating women in the University of Cambridge collections". The work of Rosanna Evans, this account was indeed fascinating to us.

I've often thought my Great, Great Aunt would make a good subject for a PhD on the somewhat subservient position of women naturalists in the Victorian era. Imagine my delight, then, to find that she has not been relegated wholesale to the dustbin of history, but in fact has an album of her work residing in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science at Cambridge. An album that inspired Evans' blog post and related work. I contacted Rosanna Evans to share the family connection and thank her for her work. A short email correspondence ensued, in which she told me:

I've often thought my Great, Great Aunt would make a good subject for a PhD on the somewhat subservient position of women naturalists in the Victorian era. Imagine my delight, then, to find that she has not been relegated wholesale to the dustbin of history, but in fact has an album of her work residing in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science at Cambridge. An album that inspired Evans' blog post and related work. I contacted Rosanna Evans to share the family connection and thank her for her work. A short email correspondence ensued, in which she told me:

"I recently gave a talk about her and the incredible album that the blog is about at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, where the album is held. The talk was to a group of people with dementia and their partners. They really responded so well to the album as well as your Great Great aunt’s incredible life story (which is much more relatable than some of the more prominent scientists and natural historians of the time!)."

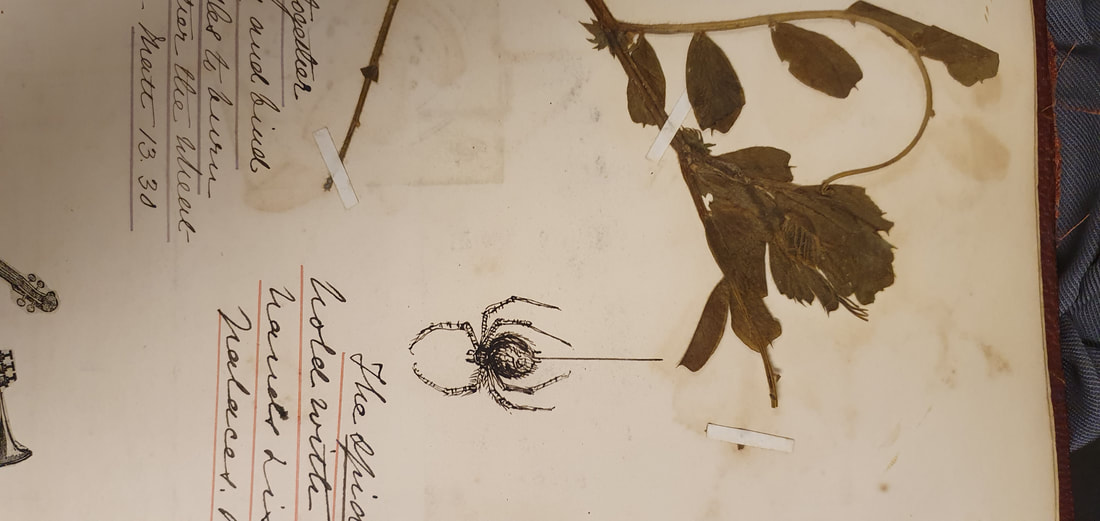

She was also kind enough to share three of the images that accompanied her talk (two above, one below), the work of Eliza Elder Brightwen, courtesy of Rosanna Evans.

Naturally, there will never be a conclusive answer to the "nature vs nurture", nor the "recycled souls" debates. That's what makes it so much fun to continue speculating. I've never been tempted to explore my ancestry via DNA sampling. But following the threads of a life spent devoted to writing and natural history? That's another story!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed